Designing an MPA Network

To protect and manage a large marine ecosystem such as the Arafura and Timor Seas (ATS) region is no easy feat. One tried and tested method is to focus efforts on High Conservation Value Areas (HCVA). In recent years, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), and especially ‘no-take zones’, have become popular tools employed by regional managers around the world, in their attempts to maximise conservation gains.

A well-designed and effectively managed MPA can protect biodiversity, increase ecosystem resilience (especially in response to fluctuations in climate and ocean chemistry), enhance fisheries productivity, and address local threats (Green et al. 2014, 2019). When individual MPAs are stitched together to form a network, the ecological benefits are greater; impacts can be seen more clearly after disturbances, while neighbouring MPAs can mutually replenish one another to facilitate recovery (Green et al. 2019).

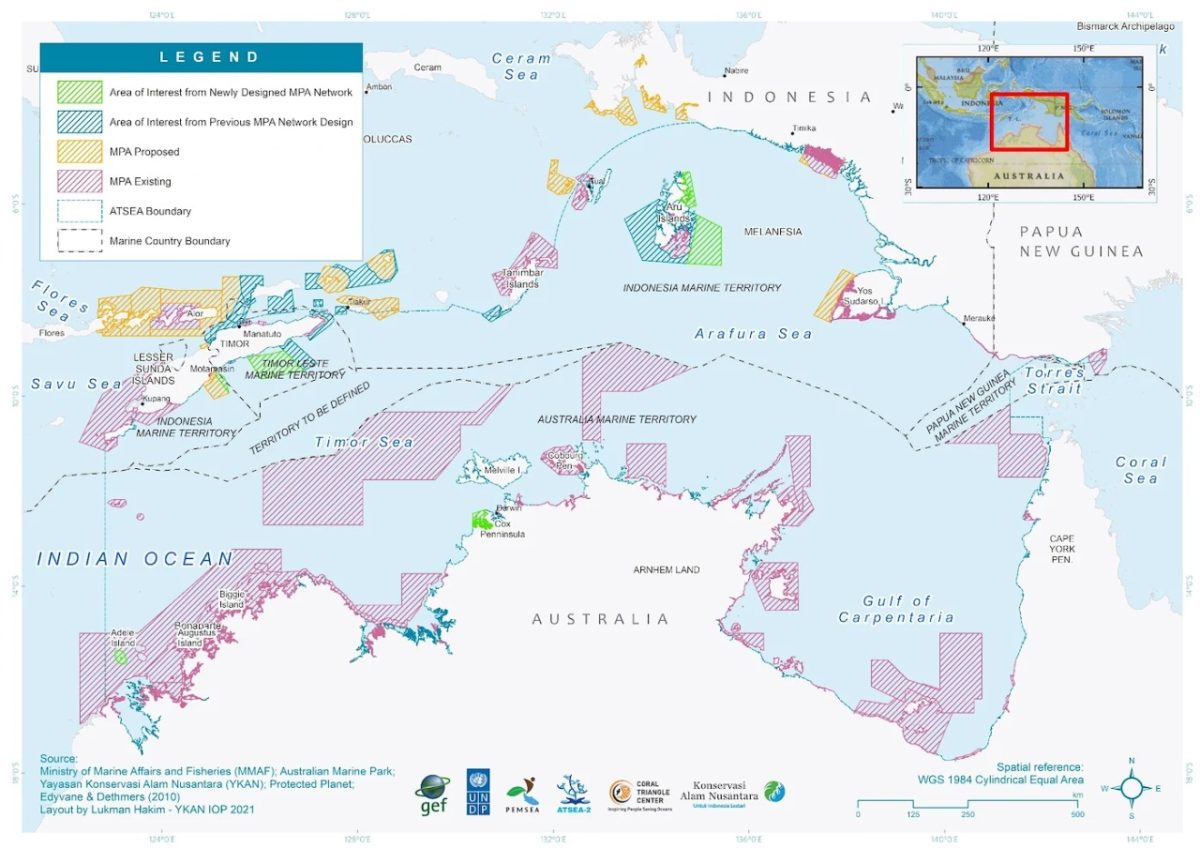

Australia, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Timor-Leste, which border the ATS region, already have existing MPAs (and spatial plans that identify potential areas for MPAs based on comprehensive planning exercises). These include:

- Australia’s Commonwealth Marine Park plan (Commonwealth Australia, 2018);

- Indonesia’s Lesser Sunda Ecoregion (Wilson, 2011),

- Fisheries Management Area 715 and six associated provinces MPA network designs (Fajariyanto et al. 2019);

- PNG’s national MPA plan (PNG Government, 2015); and

- Timor-Leste’s National Protected Area Design (Grantham et al. 2010).

However, these existing and proposed MPAs were never originally designed to form cohesive ecological networks on a regional scale. To address the gaps in national MPAs and their networks, the ATS Strategic Action Programme (SAP) set out to improve regional coordination in conserving coastal and marine ecosystems and critical habitats. In support of these priority actions, the ATSEA-2 programme set out to design an MPA network for the ATS region, by commissioning the Coral Triangle Center; Yayasan Konservasi Alam Nusantara; and Dr. Alison Green, Research Scientist at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology. The design had to consider regional biophysical, socioeconomic and cultural aspects that were not taken into account under previous national processes.

The scale and scope of this work presented a challenge; problems that were exacerbated by the emergence of Covid-19. However, despite limited time, resources and capacity for mobilisation, the team successfully created a design that built on existing MPAs and marine spatial plans from each country, using the best available data and best practices to identify gaps in existing MPA networks. Crucially, they achieved their protection targets while also minimising the impacts of resource utilisation such as capture fisheries, oil and gas mining, and shipping. The first design of the network spreads over a total area of 300,873 km2, consisting of 92 existing and proposed MPAs (covering 271,406 km2), and 18 Areas of Interest (AOI) (covering 29,467 km2), including 13 AOIs from existing plans and five proposed AOIs considered significant to the achievement of conservation goals in the ATS region.

Developing a Sea Turtle Regional Action Plan

As migratory animals with no concept of international borders or marine territories, six out of seven sea turtle species can be found in the ATS region. These are the green (Chelonia mydas), hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata), loggerhead (Caretta caretta), leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) and flatback (Natator depressus) turtles. In this region, sea turtles play an important ecological role by cropping seagrasses, foraging for sponges on coral reefs and acting as top and middle predators in marine ecosystems. For many coastal communities, they also hold customary and traditional value for food, trade and ceremonial practices.

However, sea turtles in the ATS region are faced with multiple threats: fisheries bycatch, ghost nets, predation, traditional turtle take, illegal turtle take, egg collection, climate impacts (i.e. storms, temperature, erosion) and light pollution. Therefore, just as in HCVAs, sea turtles in the ATS region would also benefit from regional conservation action being taken.

Dr. Nicolas Pilcher, senior sea turtle biologist and Executive Director of the Marine Research Foundation, prepared a sea turtle status report for the ATS region, which consolidates information on the distribution, migration, genetic structure and population trends for the six sea turtle species found in the region; the various threats that they face; and the existing legal infrastructure that supports their protection and conservation. Based on the status report, Dr. Pilcher developed a draft sea turtle Regional Action Plan (RAP) which can guide ATS countries in developing or implementing their respective national sea turtle conservation programmes. The RAP complements existing national plans – such as the Australia Recovery Plan and Indonesia National Plan of Action – but is tailored specifically to meet regional needs. It builds on IUCN Regional Action Plans and the Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation and Management of Marine Turtles and their Habitats in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia (IOSEA MoU) Conservation and Management Plan.

The RAP features eight thematic areas, each of which targets a certain country or countries. For Australia, Dr. Pilcher noted the importance of strengthening indigenous community management, while also assessing and mitigating bycatch in northern Australia fisheries. For Indonesia, he focused on assessing and mitigating bycatch in the Arafura Sea prawn fishery, and conducting baseline surveys of nesting and take, with particular focus on the Aru Islands. Baseline surveys of nesting and take For Timor-Leste were also recommended. Next, for Papua New Guinea (PNG), he highlighted the need for assessments of turtle take and an indication of population origin. Finally, for all countries, he underscored the importance of preventing fishing equipment from being discarded, and focused on developing a funding strategy for the implementation of the RAP.

Read more here